Under the direction of Yauhen Korniag productions consistently stand out like true Everests amidst the flat and monotonous theatrical landscape of contemporary Belarus. Since his very first student work, "NoDances," the author has been noted by the intellectual audience and consistently fills the auditorium to capacity. Tickets for his premieres are sold out months in advance within the first hours, and lines at the box office form long before opening.

Цяпер ён стаў галоўным рэжысёрам Беларускага дзяржаўнага тэатра лялек. Але яго новы спектакль «Zabalotsye» тtriumphantly started its journey at the capital's RTBD – a theater that is closely tied to Yauhen Korniag's main works at the moment.

So what is it about this young and unique author that attracts the audience?

"Zabalotsye" precisely provides another good opportunity to answer this question. The play has become the final installment in the trilogy about Belarus and Belarusians, started by Korniag four years ago with his famous play "Marriage with the Wind." Two years ago, there were no less significant "Touches." And now, finally, the concluding statement, a period that looks like an impressive exclamation mark.

Yauhen Korniag, like no other Belarusian theater director, knows how to stay relevant while expressing eternal themes. "Zabalotsye" and his entire "Life and Death" trilogy are precisely that kind of statement. These three productions are a journey beyond consciousness and subconsciousness, performances that take Belarusian theater and its audience out of their comfort zone, offering a long-awaited spectacle for the intellectual audience.

"Zabalotsye" continues the tradition of its predecessors, being entirely based on Belarusian folk songs. Upon entering the theater, the audience is greeted with a program-songbook featuring 17 songs, from the introductory pagan chant "Come, Ancestors-Guides..." to the final summation of the entire rich national idea "And in this world, everything is our wealth." Thus, the genre of Yauhen Korniag's new play, "Zabalotsye," is labeled as a "song in one act," as indicated on the posters. Music is an extremely important part of the play: folklore here loses its museum-like character and stirs the audience's subconscious.

The choice of folk songs as the basis of the play in "Zabalotsye" once again answers the question of whether theater should be national. Moreover, the folkloric foundation does not turn Korniag's trilogy into an ethnographic panorama. All of the director's works are both progressive in content and in their stage embodiment. Together with the composer and, as indicated on the poster, the musical director of the production, Kateryna Averkava, he creates something fantastic, completely unlike even the boldest conception of a modern performance.

The native theater, and with it the audience, is so accustomed to the theater of Chekhov, Strindberg, and Stanislavski, a theater of dialogues, monologues, and conversations—long, theatrical ones—that any non-standard production looks like an extraterrestrial invasion. Yauhen Korniag's productions, including "Zabalotsye," are no exception; they are built on a completely different principle. In his own internal theater, the director is both the playwright and demiurge, having abandoned the standard textual basis. He is the creator of his texts—visual rather than literary. Here, sound and movement take precedence. It's no coincidence that the original director-creator also works easily in puppet theaters, where the visual element takes precedence.

"Zabalotsye" is indeed a cohesive and densely packed spectacle, where individual episodes are strongly interconnected and form a unified grand performance. For the consciousness of today's audience, shaped primarily by visual culture, especially cinema, such an approach appears most effective. "Zabalotsye," like all of Korniag's plays, runs without intermission and consists of a sequence of these song-episodes.

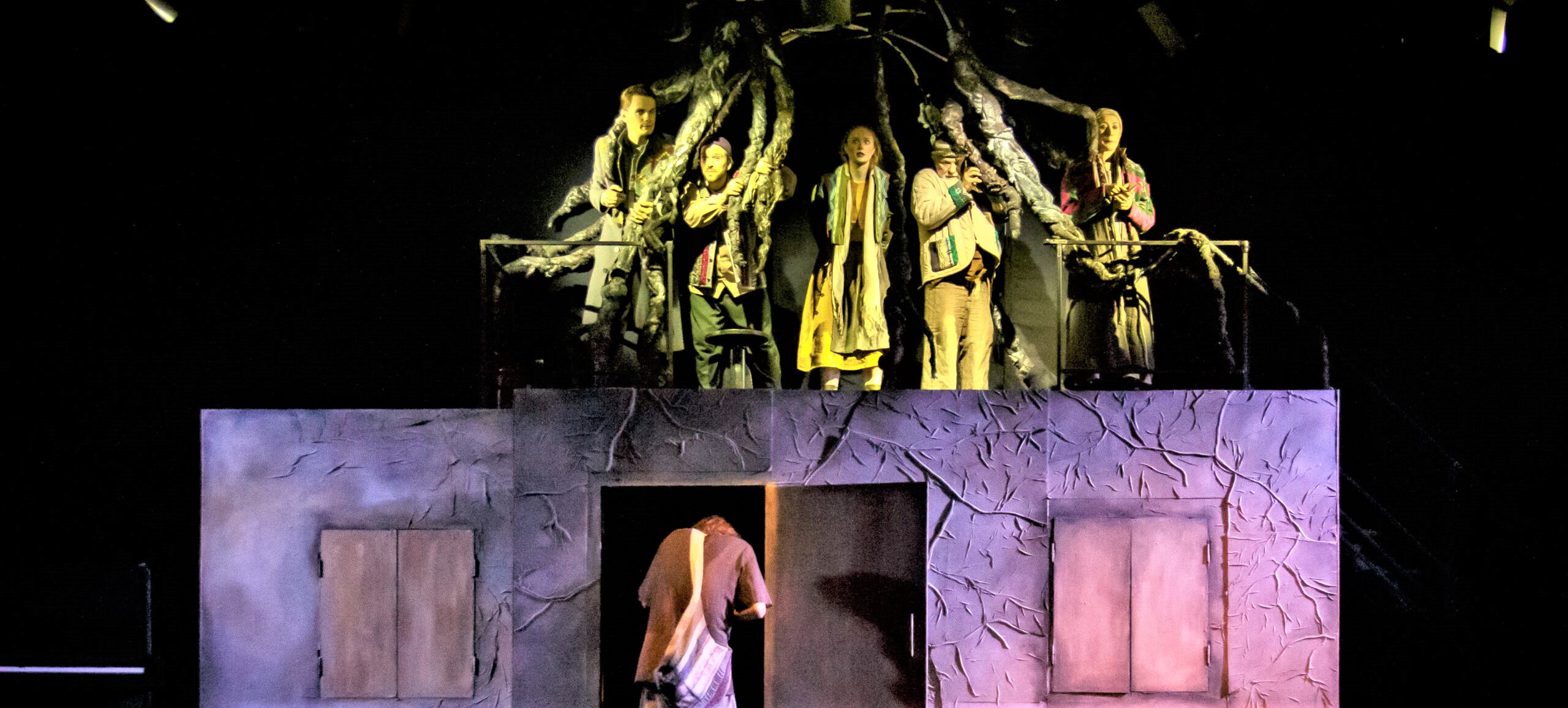

The last ones must not only be heard but also seen. Set designer Tatsiana Nersisyan, like Kateryna Averkava, a consistent collaborator of Yauhen Korniag, has condensed all events onto the tilted surface leaning towards the audience, representing the fictional village of Zabalotsye. Despite being set on a hill-guesthouse adorned with candles, where the living meet the dead, the Belarusian world unfolds as a mysterious space in cold colors. The texture of rough-hewn soil, a national ornament, in "Zabalotsye" is evident not only in the décor but also in military belts into which both male and female characters are wrapped in turn. The imaginary Belarusian Zabalotsye here seems either covered in ashes or the last clumps of earth, intertwining with the deceased.

In this production, unlike any other of Korniag's works for dramatic theater, the visible link between the director and puppet theater is apparent: various folksy details like ritual songs and folk games play as significant a role as the live performers. Direct elements of puppet theater also appear on stage in the form of archetypal figures like dogs and cows, typical of Belarusian villages. Even the actors themselves are manipulated on stage, with Korniag literally playing with them as if they were giant puppets.

"Zabalotsye" also rejects words in favor of music, specifically songs and dances. This transforms "Zabalotsye" into a complete meditation or some sort of Christian ritual in which the audience themselves participate. Ritual Belarusian songs accompany deliberate events on stage. "Zabalotsye" appears as a grand panorama of national rituals, with the main one being burial as a transition beyond closed doors—a memory that remains more vivid than others.

Actors and actresses here demonstrate mastery over their voices and bodies. The ensemble of the RTBD troupe, composed of the best artists in contemporary Belarus, shines in "Zabalotsye," where Yauhen Korniag allows each of them to shine.

Fifteen bright performers of different experiences and ages form a brilliant ensemble. Each one is a vivid individual yet plays an essential role in the complex organism of the production. "Zabalotsye" begins with the introductory lament-call of the heroine Galina Charnabaeva. Each performer has their solo moments and duets. The individual episodes become true masterpieces of acting mastery and directorial creativity.

The voices come together in a choir in various combinations—a vocal feat demanded by Korniag's actor-musicians no less than physical prowess. The performers' movements are enchanting—Korniag uses pantomime techniques extensively. Each episode-scene is constructed with maximum complexity and perfection. The unreserved physicality—actors are almost constantly in motion—serves as a symbol of maximum sincerity and openness: in that world, one cannot hide behind a facade, titles, or regalia.

«Забалоцце» больш за іншыя спектаклі Карняга прасякнуты духам містыцызму. Сімвалы і ўмоўнасць тут адыгрываюць куды большую ролю, чым нейкія дакладныя думкі і вывады. Кожны з гледачоў абапіраецца на свае эмоцыі ды асацыяцыі. Адно несумненна: «Забалоцце» ўяўляе сабой ці не ўсю тысячагадовую гісторыю беларускага народа. Але мікрасюжэты, з якіх складаецца дзея, гранічна вобразныя, яны не трымаюцца нейкіх пэўных дэталяў.

Афіцыйна пастаноўка прысвечана трагедыі маці, якая не дачакалася з фронту васьмярых сыноў. Такіх сюжэтаў, аднолькавых нават у лічбах, гісторыя ведае адразу некалькі, і не ўсе яны родам з Беларусі ― у дадзеным выпадку тое не прынцыпова. Абавязковыя адсылкі да вайны тут выглядаюць ужо ці не дзяжурным спосабам сучаснага беларускага тэатра пазбегнуць цяжкасцей з чыноўнікамі пры ўзгадненні тэмы для спектакля. Адзінае, што можна сказаць: у «Забалоцці» зусім няма вайны як такой. Ёсць архетыповы беларускі сюжэт: жанчыны хаваюць сваіх мужчын — мужоў, сыноў, — што загінулі падчас вайны, паўстання, рэвалюцыі. Менавіта дзе і як загінулі ― не так істотна. Галоўнае, мужчыны тут ― адабраныя, разлучаныя, ахвяраваныя.

As in other productions by Yauhen Korniag, one of the main themes in "Zabalotsye" is male vulnerability. However, in his previous works, Korniag has addressed contemporary male issues. "Zabalotsye," it seems, encapsulates the centuries-old tragedy of Belarusian men forced to submit to foreign will. Even against the backdrop of the general resilience and audacity of the performers on stage, the male characters here appear particularly helpless. Hence, the overarching theme of "Zabalotsye" is tragic objectification, rather than the subjectivity of Belarusians as individuals and, arguably, as a nation.

A certain evil, foreign will, generation after generation, takes Belarusian men away from Belarusian women - mothers, daughters, wives. And Belarusians can do nothing to stop this global evil and injustice. It's a silent women's march, without complaints, without protests, it's a song about tragic fate.

Associations of the ensemble of performers with an ancient Greek choir are not entirely inappropriate here. People from "Zabalotsye" become puppets in the hands of an unseen tragic fate. And waiting for God to intervene is in vain. Like the hero who suddenly comes and saves everyone once and for all. Yauhen Korniag allows no false notes in the play, and likewise, no unnatural optimism in the finale. But the audience still expects the most genuine catharsis. In the epilogue of "Zabalotsye," when the famous "fourth wall" disappears, the performers join the audience, and everyone on this side of life applauds those who invisibly protect Belarusian land.

Photo by / www.rtbd.by