Andrey Dukhovnikov has not only remained in Vitebsk after his studies but also fallen in love with this city, capturing its images in numerous artistic expressions. He also became one of the initiators of the famous Museum of the History of the Vitebsk People's Art School, where Marc Chagall taught, and where Kazimir Malevich came with like-minded individuals, developing the theoretical foundations of the avant-garde style suprematism.

VIRTUAL EXHIBITION "FORMULA OF THE CITY OF ANDREY DUKHOVNIKAV"

We talked with the artist and former director of the Vitebsk Center for Contemporary Art about the challenging path to creativity, the source of inspiration, and the history of the Vitebsk avant-garde. And also about his participation in the London Art Biennale, where his graphic work "Two Souls" was accepted

A brief history: The official opening of the Museum of the History of the Vitebsk People's Art School (5a Mark Shagal Street) took place on February 9, 2018, in the building where the Vitebsk People's Art School (VNKhU) was located from 1918 to 1923. The school was established at the initiative of Marc Chagall - the commissioner of the Collegium for Art Affairs of the Vitebsk Province - and became the first state pedagogical institution of artistic profile in Belarus. The museum opened on the eve of the 100th anniversary of the school's founding. The reconstruction was carried out according to the preserved plan of the 1923 building.

THE JOURNEY TO VITEBSK AND ART

–How did your artistic journey begin? What life paths led you to Vitebsk and the art and graphics faculty of the local university?

– I was born in the town of Lenger in Kazakhstan. My mother is from the Voronezh region, and several generations of her family were teachers. And my father was born in a camp in the village of Letovachnoye in Kazakhstan. My grandfather was Korean. (The Korean minority in Stalin's USSR was subjected to repression, including being sent to labor camps. -- Ed. Artcontext.) By the way, according to family legend, an Orthodox priest gave him the surname Dukhovnikov.

My father died when I was five years old. And my mother remarried a Belarusian who stayed in Kazakhstan after serving in the army. We lived in a settlement of geologists (South Kazakhstan Oil Exploration Expedition).

When I was in the ninth grade, we moved to Belarus.

My mother persuaded me to apply to the philology department in Mogilev, but I didn't get in and applied to a library technical school instead.

I was drawing constantly from childhood, although everyone around me kept saying, "Andrey, there's no such thing as a profession of an artist!"

Everything changed for me in the army when I served in the city of Vladimir. I met restorers who worked on the Assumption Cathedral. They let me onto the scaffolding, and I saw the frescoes by Andrei Rublev, the same ones from Tarkovsky's film. And at that moment, I realized that I wanted more than anything to become an artist.

It's a very special story to find yourself alone with Rublev in the cathedral. And the path led me to Vitebsk. During my studies at the art and graphics faculty, I drew almost 24 hours a day.

Then I went to teach at school because of my genes, because several generations of my ancestors were teachers. I wrote a new program on art history. At that time, in the 1990s, it was possible to write individual programs.

Those were wonderful years. I am still in contact and am friends with my students, although they have scattered all over the world. But then my subject, art culture of the world, was canceled. I started working as a designer and in 2000 developed a course on teaching computer graphics. In 2005-2006, my students and I participated, and in 2006, we won an international competition with a computer program dedicated to Vitebsk. We animated Vitebsk, showed it from a bird's eye view, made it possible to enter every building we marked on the map. We also brought Marc Chagall's paintings to life and told the city's history.

After this victory, I met with the Minister of Education. I said I wanted to combine animation and programming and even showed him a ready-made program. He said, "Cool, you should go to the Institute of Improvement." However, I was quickly put in my place there, like, "What are you doing? Who are you?" In the end, I returned to Vitebsk and soon went to work in the Center for Modern Art. And since then, from 2009 until September 14, 2023, I have been the director of the Center for Modern Art.

THE MUSEUM IS ABOVE ALL A UNIQUE HOME

– - How did this wonderful story of creating a branch of your Center - the Museum of the History of the Vitebsk People's Art School - begin?

– The building where our museum is located was built in 1914 by the wealthiest man in Vitebsk, banker Vishnyak. In 1918, the house was transferred to an art school, which was headed by Marc Chagall. In 1920, Kazimir Malevich arrived there and developed his own teaching system. As the founder of Suprematism, Malevich created the UNOVIS group in the city, implementing his ideas with the help of Vitebsk students. He worked here for two and a half years, wrote several philosophical works during this time, and created a unique school of world-class art that laid the foundation for modern art, architecture, and design.

– There seem to be almost no works and documents about the activities of UNOVIS in Vitebsk... What was the basis for the museum then?

– The Vitebsk Regional Archive has a lot of documents about the school, including all the statutory documents of UNOVIS. Specialists work with them and constantly make new discoveries. However, the main exhibit of our museum is the building itself. The house miraculously survived, enduring wars and Communists. Our idea was to breathe life into it. To return the seemingly lost pages of culture to Vitebsk and the country. These are very important pages! They include both Vitebsk and Belarus in the context of world culture. There's no arguing with that.

And we did it, we restored the building.

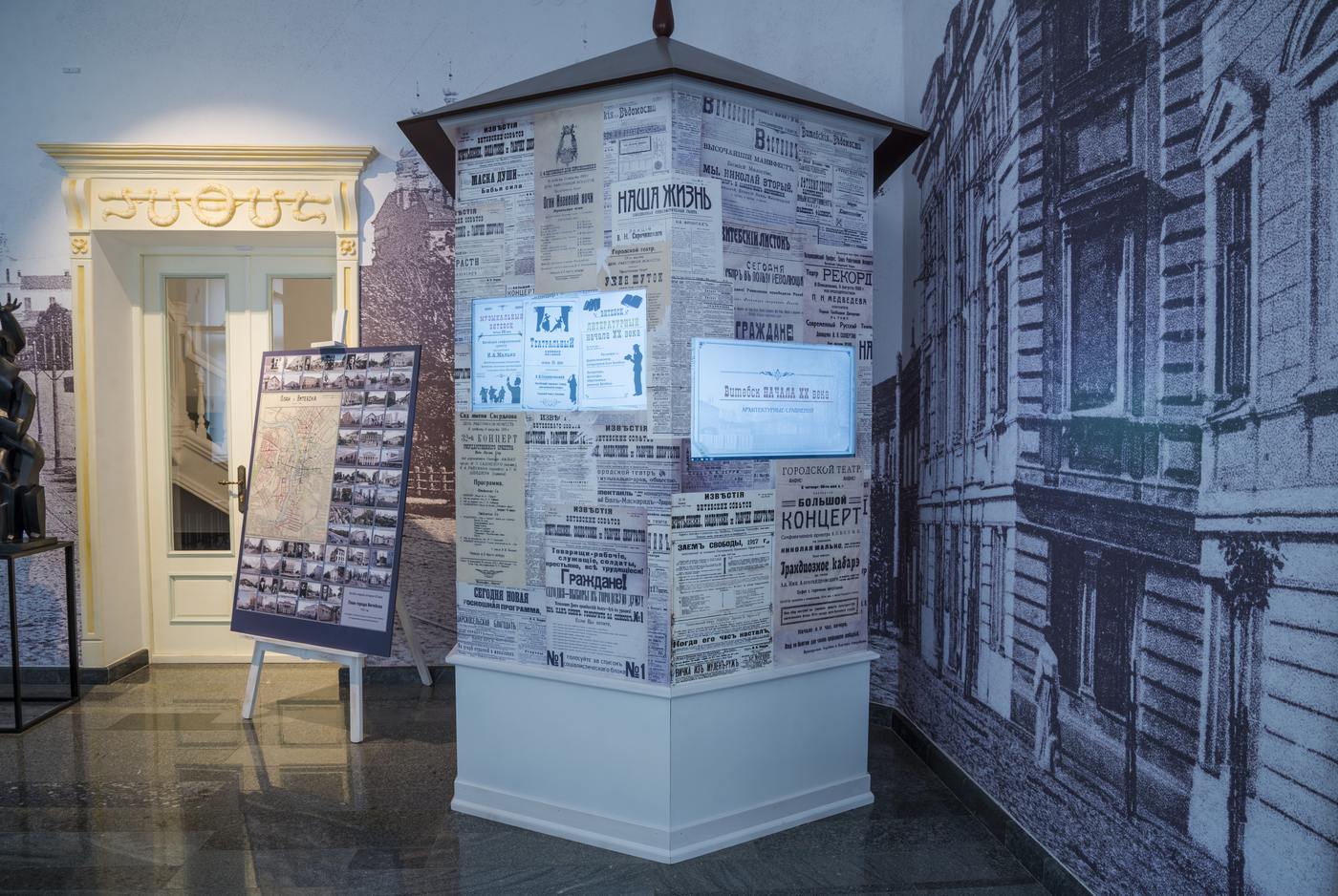

I must say that only the city budget money was used. During the design, the idea arose to combine material history with virtual history. And with the help of multimedia, we began to tell the story of the early 1920s. It's a narrative museum, a storytelling museum.

– Was there an attempt to recreate workshops, classrooms?

– No, it was impossible to do that. We recreated the staircase, the ancient molding...

In addition to the school, there was also a clinic and a children's home there. But our story is mainly about the school.

The main goal was to bring back that avant-garde, suprematist history to Vitebsk.

So, in all world encyclopedias on the avant-garde, this house, this school is mentioned, where Malevich taught according to his system, but only specialists know the details. And we tried to make this knowledge available to the wider public.

– The museum has many functions: for example, exhibitions are held here...

– Yes, we have created a small (120 m2) exhibition hall in the museum. This hall is probably the most prestigious in our country. After all, exhibiting one's works in a place where the history of modern art was born is a special pride!

Of course, we cannot exhibit projects there that are outside the context of this Vitebsk theme, such as landscapes or decorative art.

We organized exhibitions of experimental art or those related to the theme of the avant-garde. For example, we showcased works by Osip Tsadkin and brought works by Rodchenko from Moscow. Currently, Matvey Basov's works are on display.

– What research do the museum's researchers conduct?

–The museum staff research the topic of Vitebsk's history in the early 20th century. We study Vitebsk at that time, and even more narrowly - the district where the museum is located. It turned out that we privatized this topic, and the main object and theme of the research is the house and what happened in it.

– The symbol of Vitebsk is now"Slavianski Bazaar", however, it seems that suprematism, Malevich, Chagall, and the Vitebsk Art School should become bright and real symbols of the city.

– Our museum is not part of mass culture, although we live in a world where this mass culture dominates. We are working on creating the brand of the school, and successfully, as the number of visitors, those people who are close to and interested in this topic, has significantly increased. What we show is not very clear to the general audience, so we have been doing a lot of educational work, proving why the avant-garde of the 1920s is a national value that no one in Vitebsk will take away anymore! And little by little, it all worked out.

– Suprematism is a bright, recognizable style. How did you introduce this period into the history and modernity of the city?

– First of all, yes, it's beautiful, stylish, and modern. The geometric abstraction of the early 20th century is the basis of world design.

Minimalism is now a fashionable trend, and we are trying to develop this suprematist history. We develop souvenirs. Mostly these are works by our Vitebsk designer, who is well versed in the subject and has made it so that our museum is known far beyond Belarus. There isn't a single item in our museum made in China.

We have defined several branded positions. For example, the "Vitebsk Tram." The UNOVIS artists painted the Vitebsk Tram in 1920. And, in general, it is a very progressive form of transport in European cities. We made a stool the symbol of the museum. In the photos of those days, it is seen that the house was furnished with old furniture, and among this luxurious furniture, there were many stools for artists to work in the workshops.

Therefore, by furnishing our museum with furniture, we focused specifically on stools. We have four types of them - specially designed, of different heights. After all, this is the most democratic furniture.

– Maybe you have some quirks in working with museum visitors?

– We hold many workshops, for example, we painted stools, conducted quests in the museum. I developed a tour for children during which we teach ten new words related to suprematism. And much more.

– And how do you work with urban space? Vitebsk suprematists were actively involved in decorating the city for revolutionary holidays...

– Through our graffiti artists, through construction companies, we tried to ensure that suprematist murals were created on the houses. Several such murals have appeared.

.jpg)

.jpg)

On Mark Shagal Street, where our museum is located, there are murals with replicas of Malevich's works. Currently, houses are being built in new neighborhoods that will be decorated with suprematist murals. It is important that suprematism does not become boring, does not turn into a cliché...

.jpg)

– If interpretations of suprematism go into decorativeness, there is such a threat. But if you perceive the style as the basis of modern artistic language, then this may not happen.

– Yes, it needs to be done clearly, unobtrusively, and very consistently.

Creative Work

– Your works as an artist are very rhythmic and balanced. And quite minimalist in terms of color... It's interesting, what method do you use to create your graphics and paintings - do you carefully plan your compositions or do them spontaneously?

– I am an impulsive person, so I create works intuitively, like breathing... I literally work like I breath. I found a formula for myself: draw on the exhale. Today, I don't care where I work, with what materials. I have found two or three technical tricks that I use in both miniature and large works, and that's enough for me. I work with oil, pastels, and sanguine, but not only on paper, but also on canvas.

– In your works, you constantly strive to capture the essence of the city. Your images are rhythmic, compact, dynamic. Are they based on specific landscapes or are they a product of imagination?

–This question is constantly asked of me because people look for something familiar in my paintings. I have depicted Vitebsk inside and out. I have many realistic images in which I explored architectural interactions. But at some point, my colleague Ales Memus called these works tourist pictures. And I realized that I had indeed descended into some tourist representation of Vitebsk, although such things were undoubtedly selling. And I stopped depicting this city literally; it became uninteresting to do so.

I love Poland, I have drawn Vilnius a lot. I seek and find graphic formulas for various cities. It's interesting and allows me to move forward.

In other cities, I am primarily interested in people. The city means something if there are people familiar to me in it.

When I come to Berlin, I go rather to friends then to museums. People are the most important.

– However, in your works, human figures are present as extras...

- Yes, in my works, people are, so to speak, symbols...

My works are my inner monologues. I talk about things I'm thinking about at that moment, and sometimes they can't be conveyed in words.

Some of my works are minimalist - just a thought and a half. Some are overloaded because there's a lot to say.

I'm also concerned with plastic solutions - movement, emphasis, color.

This approach doesn't work on large canvases; the viewer won't understand your impulse if you don't fine-tune your message to the millimeter. Large works involve a lot of physical labor.

–How did you become a participant in the London Art Biennale, which opened in Chelsea on July 27th?

–Very simple: I sent several paintings by mail. And on the spot, this painting was simply taken to the Old Town Hall in Chelsea.

I sent several works, but only one was accepted.

– Did you attend the opening later?

– It didn't work out, I was not given a visa. So I had to watch the exhibition only on video.

– Why is the artwork from the Chelsea exhibition called "Two Souls"? Formally, there is a balance of equilibrium embodied there...

– To be a whole person, you need a soul, and for this wholeness to be complete - you need two souls.

And balance is needed not only in life but also in art.

VIRTUAL EXHIBITION "FORMULA OF THE CITY OF ANDREY DUKHOVNIKAV"